Filipino opera, sung by diverse American cast of singers, makes a mark in Chicago

Posted on May 26, 2012

CHICAGO: Talk about transnational. And diversity. An opera with a Latin title that talks inTagalog. But is sung in a U.S. production by non-Tagalog singers. A Filipino opera written by a prolific composer who advocated for a nation’s ideals through his music creations:Felipe de Leon. A classical opera version of a historical novel by Jose Rizaltracking the twilight of Spanish colonization in the Philippines. A novel that rocked that country into political consciousness in the late 19th century. A country whose classical opera tradition borrowed greatly from the introduction of European opera.

On May 26 and 27, 2012 at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance, da Corneto Opera, an all-American opera company in Chicago, tackles Felipe de Leon’s opera Noli Me Tangere. This U.S. premiere, under the auspices of KGB Productions, will be sung in Tagalog (with English supertitles) by performers for whom Tagalog is a foreign tongue. In fact, only 6 of the 60 opera singers are Filipinos.

With a libretto by Guillermo Tolentino, De Leon’s 1957 opera Noli Me Tangere is not the first Filipino opera ever written. (That honor belongs to Sandugong Panaginip, a 1902 work with a libretto by Pedro Paterno and music by Ladislao Bonus.) Because of its Rizal provenance, it has enjoyed a longer life than most Filipino operas. Completed in 1950, it has been performed in 1957, 1987 and last year to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Rizal.

(Update: After posting this story, I learned that Dulaang UP’s Alexander C. Cortezrecently directed the same opera in Manila. Manila Bulletin Online had an article about this Manila production. Click here. So did Philippine Star here. )

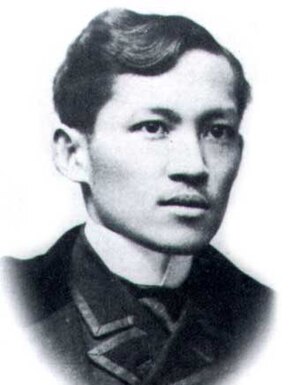

Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, is a role model of young Filipino men. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

DaCorneto Opera’s Chicago rings the bells of other significant timelines. May 2012 is the 100th birth anniversary of composer de Leon. And 125 years ago, Noli Me Tangerewas first published in Berlin (it was written in Spanish). And May is Asian American Heritage month.

Steven Wallace, an African America singer, portrays Noli‘s lead role of Juan Crisóstomo Ibarra y Magsalin, who returns to the Philippines after seven years of academic studies in Europe. He plans to wed his betrothed Maria Clara, sung by Mila Koleva (who is originally from Bulgaria) and to fulfill his father’s dream of opening a school.

Crisóstomo Ibarra’s archenemyFather Dámaso – sung by Alvaro Ramiezer, a native of Mexico – is the notorious and imperious priest who has a vendetta against the Ibarra clan. Damaso is Rizal’s symbol of the Spanish clergy who covertly fathered illegitimate children.

The evening’s conductor? Her name is Lucia Matos. She’s Brazilian.

Karrel G. Bernardo, a Fil-Am performer and the main producer of this Noli opera, tackles the supporting role of Elias. “Out of 60 opera singers, only 6 are Filipinos, staged with full orchestra,” Bernardo says in an interview. “It’s so heart warming to listen to them sing Tagalog. This is the first time our musical heritage will be performed and offered to the diverse crowd in Chicago. The most important is for the second generation Filipino Americans who were born here and have no idea who Rizal was, and what this novel is about.”

The Noli performances culminate a series of Asian American Heritage-related events. All of which were programmed under the banner of “Diversity Through the Arts; Bridging Cultures“ www.DiversityThroughTheArts.org.

Noli Me Tangere did not directly spark the Philippine Revolution. When he wrote it, Rizal actually advocated direct representation to the Spanish government. Politically and symbolically, he saw Spain as the father and the Philippines the daughter. The novel, however, packed powerful ideas and lacerating truths. It described, satirized and exposed the ills of the Philippine colonial society; in particular it reveals and chronicles the oppression of Spanish rule, as well as the corruption and abuse by the Catholic clergy who insisted that the Noli was a subversive work.

Eventually Rizal himself was branded a subversive. He was executed by the Spaniards in 1896. His Noli played an instrumental role in creating the sense of a unified Filipino national identity and consciousness, but it was Rizal’s execution that was one of the causes of the Philippine Revolution. Although the Americans eventually followed the Spaniards as the country’s foreign colonizers, Noli Me Tangere (and its sequel El filibusterismo) opened the eyes and minds of the Filipinos to the possibility of sovereignty, independence and revolution.

In 1956, the Congress of the Philippines passed the Republic Act 1425, more popularly known as the Rizal Law, which requires all levels of Philippine schools to teach the novel as part of their curriculum. Noli Me Tangere is taught to third-year secondary school students, while its sequel El filibusterismo is taught to fourth-year secondary school students.

If Felipe de Leon were alive today, it would most surely please him to see non-Filipinos attempting to convey and sing one of his most treasured creations. A prolific writer and music education, De Leon cared very much for Filipino folk music and cultural traditions. He successfully turned Rizal’s El filibusterismo into an opera as well. He also wrote numerous zarzuelas, overtures, suites, symphonic poems, chamber works, choral music, concertos, piano solos, band music, film music, children’s songs and Christmas carols. He founded the Pambansang Samahan ng mga Banda sa Pilipinas (Philippine Band Association) and the Filipino Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.

De Leon is today remembered as a prime advocate of nationalism throughout his life. Martial Law babies still recall singing his patriotic song “Bagong Lipunan.” It was fitting, therefore, that on December 8, 1997, President Fidel V. Ramos granted him the highest honor a Filipino artist can receive, the National Artist Award for music.

No comments:

Post a Comment