On the jeepney. (All photos: Will Hatton)

The wind whipped my hair into a frenzy as I sat taking in the landscape. Below me, a dozen Filipinos lounged with regimented discipline on hard wooden seats. I sat alone atop the brightly painted public bus, called a jeepney. Luminous green paddy fields streamed away from me in all directions. I had been traveling the world for over seven years — I went where I wanted and did as I liked, provided I could scrape together the money. For years, the Philippines had called to me: perfect beaches, friendly people, tropical jungles, and ancient traditions — one of which I was fascinated with.

I was leaving Sagada and heading deep into the tribal territory of the Kalingas. I was on a pilgrimage to visit the legendary Whang Od, a 97-year-old who is the last woman in the world to claim the title of Mambabatok — the tattoo master. For decades, Whang Od has kept the traditions of the Butbut tribe alive by tattooing with thorns, charcoal, and a small bamboo hammer. Now, I hoped to join the privileged few who could say they had been tattooed by the last Kalinga tattoo master. Unfortunately, it was not exactly simple to make an appointment with Whang Od — one simply had to turn up and hope that she felt like tattooing a foreigner (traditionally, Kalinga tattoos are reserved for Kalingas only).

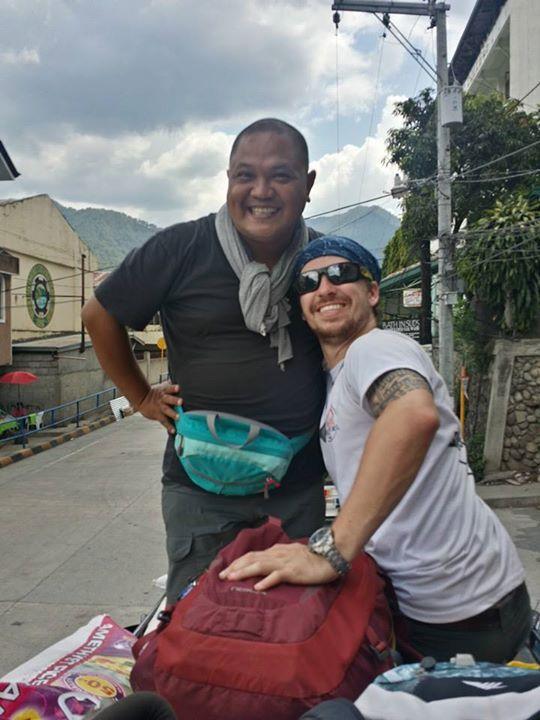

Hanging with Pot Pot.

The jeepney spat me out in a dusty frontier town called Bontoc. I was meeting a Filipino guide who was going to help me get to Whang Od and act as a translator once I arrived. I had absolutely no idea what he looked like, so I smiled stupidly at anyone who walked toward me. I hoped he would find me. It shouldn’t be hard, I reasoned — I was the only white face for miles. I sat snacking on fresh mangoes and chatting to a bored policeman until my guide, Pot Pot, finally arrived. Pot Pot is a constantly smiling, always giggling man in his late 30s who somewhat resembles a small Buddha with his shaved head and twinkling eyes. He thrust a cold Coke into my hand and urged me to climb atop yet another jeepney with him. In a belch of exhaust fumes, we left Bontoc behind.

Racing further into the country, the jeepney took hairpin bends with reckless abandon, bouncing us along as we climbed into the mountains. We passed deep ravines and soaring hills, countless paddy fields, farmers carrying goods to market, children playing in the road, herds of hogs snuffling in the undergrowth, and tiny hamlets, all the while clinging to the tiny space between the road and a vertical drop. The jeepney took us as far as possible before the road dwindled to nothing and we got out to continue on foot.

I shouldered my pack and we set off into the jungle, following a gaggle of children with extremely unhappy chickens tied to sticks. Slowly but surely, we left civilization behind and traipsed further from the road and higher into the hills. An hour later, I was dripping with sweat and we could see a small village ahead perched atop a particularly steep-looking hill. I turned, catching the last rays of the sun as they slipped across the valley, and decided we’d better hurry up. It was going to be dark soon.

We arrived at the village without warning: One minute we were on the lonely path, and the next, we’d burst from the jungle and were standing next to a wooden shack with a tin roof. Animal skulls and chicken feet hung from every square inch of a nearby house. The villagers came out to greet us. They spoke only limited English, but, luckily, Pot Pot acted as a translator. Before I knew it, I was whisked away by a friendly family and shown a place where I could lay my pack and sleep for the night. I crashed almost immediately, exhausted and all-too aware that tomorrow I would finally be meeting with Whang Od.

Whang Od in her hoodie.

She didn’t look like she was 97. She didn’t move like she was 97. She was sprightly, humorous even, and smiled from beneath a heavy black hoodie — the kind of thing a gangster rapper might wear. Pot Pot conferred with Whang Od, introducing me with a grand sweep of his arm. She looked at me with twinkling eyes and then went back to teasing Pot Pot and poking his belly. She had consented, I would be tattooed.

I had spent most of the morning agonizing over what tattoo to get and, in the end, decided on a fern — a symbol of rebirth and (I later found out) fertility. I was going to be one fertile dude by the time this was done. Whang Od carefully outlined the tattoo on my arm using charcoal and a small stick. Next, she picked a sharp thorn and placed it carefully within another stick before glancing at me, checking that I was ready, and preparing her hammer.

Tools of the trade.

I sat on a hard block of wood, watching with grim fascination as she lifted the stick and began. Whack, whack, whack. I felt nothing. I watched as the thorn punctured my skin again and again, forcing the charcoal inside the wound, five times a second. The melodic noise of the hammer drifted across the village as a crowd of interested villagers watched to see if I would show any sign of pain. I did not, for in truth, it really didn’t hurt. I had waited years to meet this incredible women; I had traversed valleys and hiked through jungles, ridden atop metallic death vans and endured belching fumes — what were a few pinpricks to mark the successful completion of my journey?

The fertility fern.

Tiny droplets of blood formed on my arm as the design came to life in my flesh. It crawled and writhed as Whang Od birthed it with her bamboo hammer. I could think of no better way to pay homage to this incredible women and to the Philippines than to get a traditional tattoo. This was an idea I had been knocking around for years, and as I watched the design take over my arm, I knew I had made the right decision.

https://www.yahoo.com/travel/i-went-to-the-philippines-to-be-tattooed-by-a-118825720242.html

No comments:

Post a Comment