Caroline Kennedy: My Travels

Places I Have Been – People I Have Met

I had arrived in Manila almost by accident in 1968 and remained there on and off for the next sixteen years. My first decade there turned out to be, perhaps, the most bizarre in my entire life. During that short period I went through more incarnations than most people do in a lifetime.

In those few years I was transformed from budding writer and radio producer, to weekly columnist, to singer, to actress, to TV presenter, to disc jockey, to comic strip heroine, to film star and, finally, ending up annointed as a true “Living Goddess” among a former headhunting tribe in the Philippine’s remote Mountain Province.

The years I spent in the Philippines coincided almost exactly with the years in power of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. So, as a journalist, I was able to observe and write about them at firsthand. It was hard, in fact, to ignore them. They dominated every aspect of Philippine life, particularly since the imposition of martial law in 1972. There was nowhere you could look in Manila without seeing their larger than life posters on giant hoardings. There was nowhere you could go without overhearing endless conversations about them and ambitious plots being forged against them. And there was nowhere you could hide without feeling that your every move was being closely monitored by them or their cohorts. Theirs was an all-pervasive presence, neither benign nor compassionate. On the contrary, theirs was a destructive, intimidating and, for the Filipino nation as a whole, an ultimately catastrophic presence.

I spent much of my time in the Philippines chronicling the excesses of Imelda Romualdez Marcos. I think there has been nobody in contemporary history that has so aptly illustrated the saying that:

“Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Imelda always liked to compare herself with Eva Peron. In fact she took it as a compliment if anyone pointed out any similarities between her and the former First Lady of Argentina. But, despite Eva Peron’s excesses – and there were many – at least she did, in part, help her “decamisados” as the Argentine’s poor were referred to. But, in twenty-one years as First Lady of the Philippines, Imelda Romualdez Marcos did nothing for the destitute in her country.

At the time of my arrival in the Philippines the Marcoses had been in power for only three years and so I was able to see and document their rise, from fairly humble beginnings, to what has been dubbed their “conjugal dictatorship”, outlasting as they did so, four US presidents and three British prime ministers until their final ignominious defeat in February 1986.

I suppose the image that springs to most peoples’ minds when they hear the name Imelda Marcos is shoes. This is hardly surprising since it is now known she owned at least 3000 pairs of them. And it is hard to forget the TV news film, in February 1986, showing row upon row of them left behind in the Palace when she fled to exile in Hawaii.

“Three thousand?“ Imelda protested at the time, “That’s nonsense! I only had 1006!”

Imelda’s shoes have, perhaps, become the very symbol of her excesses. They are currently housed in the Imelda Marcos Museum in Manila, a museum dedicated solely to her greed, her ostentatious lifestyle and her extravagances.

Imelda may have left behind all those pairs of shoes for us to marvel at but many of us probably harbour a secret admiration for what she and her husband, the late President Ferdinand Marcos, did manage to bring with them into the United States under the term “household effects”. The official customs list drawn up when they arrived into exile in Hawaii reads like pure fantasy.

22 Crates of Cash valued at $717 million dollars

300 crates of assorted jewellery Value undetermined.

$4 million dollars worth of unset precious gems contained in Pampers diaper boxes.

$7.7 million dollars worth of jewellery, including a gold crown encrusted with diamonds, three tiaras, 65 Seiko and Cartier watches

A box, measuring 12 feet by 4 feet, crammed full of real pearls.

A 3 foot solid gold statue covered in diamonds and other precious stones.

$200,000 dollars in gold bullion and nearly $1 million dollars in Philippine pesos

Discovered among their luggage too were deposit slips worth $124 million dollars for banks in the US, Switzerland and the Cayman Islands.

A week ahead of their departure 2000 tons of gold, worth $22 billion dollars, had been dispatched to Australia but, on a tip off, was intercepted by the vigilant Australian Customs. Weekly shuttle flights, transporting crates containing money, period furniture, antiques and Old Master paintings were reported to have flown to Hong Kong during the six months prior to their downfall in February 1986.

A further $250 million dollars worth of jewellery was also confiscated from a friend of Imelda’s who was caught smuggling them out of the country for her.

And this was probably just the beginning. Over two decades later the Philippines government is still trying to locate all the Marcos assets. Imelda has not helped them. She has claimed the Fifth Ammendment. She has obfuscated. She has bribed. And she has lied. She told the Philippines commission charged with retrieving the stolen funds:

“If you know how rich you are, you aren’t rich. I have no idea how rich I am!”

Following a request from the Philippines government, the Swiss government, for the first time ever in its history of secret banking, froze all assets they suspected of belonging to any member of the Marcos family. In the past five years the Swiss government revealed the existence of yet another Marcos account, holding almost $20 billion! And so it seems quite possible that one day we might actually find out just how rich the Marcoses were.

After my arrival in the Philippines, just three years into her husband’s first presidential term, I became fascinated by Imelda Marcos and proceeded to write about her often, mainly in very unflattering terms. My best friend Betsy Romualdez, a writer and poet, happened to be Imelda’s niece and so I was fortunate to have access to many inside stories about the First Lady, more so than most Filipino journalists at the time.

I was still living in Manila in 1974 when Imelda was hosting the 23rd Miss Universe contest. On the night of the main event the beauties and the foreign Press were lined up for hours in the lobby of Imelda’s brand new Cultural Centre building waiting for the First Lady to show up. Eventually her limousine swept up the driveway and Imelda regally stepped out. As she passed down the line of girls, a bit like royalty, she stopped occasionally to shake hands with them and share a few words.

When she reached Miss South Africa she asked, “What does your father do?” The nervous young woman replied, “Daddy? Oh, he’s in the mining business!”

“That’s a coincidence ! “ Imelda immediately retorted, sweeping her arms around the magnificent lobby of her new Cultural Centre, “I’m in the mining business too! That’s mine, that’s mine and that’s mine. In fact everything you see here is mine!”

This may have been Imelda’s cynical attempt at a joke, and a handful of journalists among our group giggled politely, but it had a portentous ring. For less than 15 years later, Imelda, her husband and their cronies, would own an estimated 85% of the nation’s wealth, commerce, land, produce, dollar and gold reserves. By their departure in 1986, the country would be left reeling, bankrupt and riddled by foreign debt from which it is still recovering today.

Although Marcos had taught Imelda how to play dirty politics, her drive and ambition were entirely her own. As she succeeded in winning votes for him so he rewarded her with jewellery. She, in turn, would tell journalists and friends that these jewels were Romualdez family heirlooms she had inherited along with a palatial home, priceless antiques, paintings and a silver collection.

In the early days, during the 1965 presidential campaign, Marcos was able not only to switch from being the leader of the Liberal Party to being the leader of the Nacionalista Party but also to clinch the election. But political pundits and colleagues agreed it was Imelda who influenced the result. Marcos was a brilliant tactician, they said, but it was Imelda’s charm, persuasion and sweet singing voice that ultimately won him the presidency.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say,” a political aide told me, “that Imelda used plane, motorboat, banca and literally crawled on her hands and knees to reach each delegate who had a vote. She then swayed them with her voice, her tears and her beauty.”

For his part, Marcos wined and dined his supporters at the opulent Manila Hotel, filled their pockets with 100 peso bills and took them to expensive nightclubs. Following their inauguration, Imelda sent US presidential candidate, Hubert Humphrey, some personal advice on how to win an election:

“You’ve got to control the site of the convention,” she wrote, “you’ve got to have your people everywhere. We had the bellhops. We had the waiters. We had the elevator boys. We had the desk clerks. We had everybody talking about Marcos. But the most important thing was that we had all the telephone operators so the other side never received their telephone calls!”

The presidential election of 1963 had been the costliest, dirtiest and most vicious campaign in the country’s history, “a year long propaganda orgy”as the American Embassy in Manila discreetly described it. But the foreign press were already referring to the Philippines as the “new Camelot” and to the beautiful, young First Lady as the “Asian Jackie Kennedy.” And a few months after the election the Marcoses paid the customary state visit to America. Imelda took the States by storm. “A photographer’s delight” the newspapers called her as she sang a Filipino love song to a bemused President Johnson at a gala dinner. Washington was mesmerized. Politicians and press alike were seduced by her beauty and her charm. For the first time Imelda witnessed the power of her own personal magnetism.

The newspapers quoted her on her return to Manila saying:

“The Metropolitan Opera House – it was fabulous – those chandeliers, those paintings…My God, the Rockefellers, the Duponts, the Fords, the Magnins, the Lindsays, the painter Marc Chagall – you know he wanted to paint me. And the jewels the women were wearing… strands and strands of diamonds around their necks!….Wow, in America when they’re rich, they’re really rich!”

Back home Imelda set to work to create her own opulent environment worthy of entertaining her new super-rich friends. She began a massive building programme that, in time, came to be known as her “edifice complex” – not to house the poor and the dispossessed – but to forward her aims of making Manila into the cultural and financial capital of Asia. Neither she nor Marcos cared for the underprivileged. If the squatters’ huts presented an eyesore to her or her foreign guests, she had them obliterated with a bulldozer. She had once been poor herself and she never wanted to be reminded of the fact.

And the sad truth is that Marcos, too, cared little for the majority of his people. During his rule as president graft and corruption flourished, rural poverty became more crushing, the gap between rich and poor widened and these conditions were exploited by the emerging Communist Party. This was painful to the U.S. because the Philippines was the country America had tried to model after its own democratic image. It was where, in 1899, the Americans had fought their first counter-insurgency war in the name of protecting freedom and defeating what they saw as the growing threat of communism.

On his election to the presidency Marcos had promised a redistribution of the country’s wealth – on that he certainly delivered. But he redistributed the wealth from the poor to his business colleagues, his Army generals, his friends and his own family. Overall, by the mid-1970’s seven out of ten Filipinos were worse off economically. Real wages for workers had fallen about 30% while consumer prices had tripled. Two out of every three Filipinos were surviving below the poverty line and a staggering 40%, 21 million Filipinos, were homeless.

The per capita calorie intake, too, was less in 1976 than it had been in 1960. This, despite the fact the U.S. had provided the Philippines with more than $300 million under the Food for Peace Programme. In the 1950s Filipinos had probably been the best fed people in Asia. Now people in India, Indonesia and, perhaps, even Bangladesh were eating better than they were. 40% of all the nation’s deaths were caused by malnutrition. An American journalist visiting the Visayas Islands (near Imelda’s birthplace) in 1979 reported:

“The young patients I saw in the hospitals there seem to have been transplanted from the famines in Bangladesh and the sub-Sahara earlier in the decade. Big eyes staring from skeletal heads, matchstick limbs and bloated bellies. But they were the fortunate ones. They were receiving treatment.”

Impervious to any such domestic problems, Imelda started her infamous shopping sprees in

Rome, Paris, New York and London – at Bulgari, Harry Winston, Tiffany’s and Cartier. On October 13 1977 she parted with $384,000 for diamonds. Two weeks later on November 2 she spent over $1 million for more diamonds. In July 1978, after her third visit to the Soviet Union, nine days of spartan communism had, apparently, proved too restricting for her and she flew directly to New York for a retail therapy binge. On her first full morning there she paid out $194,000 for antiques and the following week in a one-day spree she spent over $2 million on more diamonds and emeralds. And all this on her husband’s official presidential salary of just $6500 a year!

Nothing and no one would get in her way. When the world press criticized her for being profligate, she would answer that she was only carrying out the wishes of her people.

“They want me to shine like a star in their midst. Who am I not to carry out their wishes?” she asked.

When hauled before a U.S. Congressional Committee of outraged congressmen, her charm no longer seduced them. They demanded to know where her money came from and threatened to cut off aid to her country if she continued to spend so lavishly. Back home she referred to them as “barbarians.”She compared them to the Spanish Inquisition:

“I have been to Peking. I have been to Moscow. I have been to Libya,” she fumed, “and nobody ever treated me so rudely!”

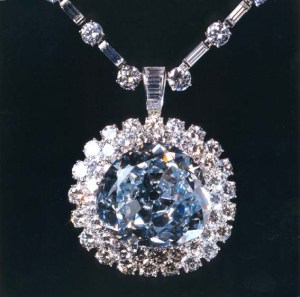

Her husband pacified her with a gift of the world’s largest blue diamond, the notorious “Idol’s Eye”, said then to be worth $5 million.

The following year while her Ferdinand Marcos was negotiating the renewal of the U.S. bases agreement and promising a massive austerity campaign at home because of the spiraling inflation and a huge foreign overseas debt, Imelda again went on a shopping spree in the US. She bought a multi-million dollar estate in Long Island, named Lindenmere. She shelled out $328,000 on more diamonds, $717,000 on a house in Hawaii, $5.3 million on a hotel in San Francisco, $1 million on another house in Hawaii and, on August 25, 1981, she bought a heart-shaped diamond for over $1million and two necklaces for $400,000.

Two days later she spent another $616,000 on antiques and, in September of that same year,

she bought the Fan Fox Samuels estate on Long Island for almost $6 million. In that period too she acquired a townhouse on 66thStreet and Madison in Manhattan and she negotiated the purchase of one of New York’s most famous landmarks, the Crown Building, on 57th Street and Fifth Avenue. In her personal collection too, I was told by my friend, Jun Gonzalez her private art restorer, she owned Old Master paintings and sculptures worth in excess of $20 million. Jun told me Imelda had invited him to the Palace to see a 12 foot X 12 foot painting by Holbein. He asked if I would like accompany him.

“How could she have bought a Holbein?” I was incredulous.“Surely, the whole world would know when a Holbein had been purchased on the international art market ? Where had it come from ? Who had sold it to her – or had she been duped – yet again?”

That was not all she owned, Jun told me. In her collection I would see Canalettos, Chagalls, El Grecos, Rubens, Rembrandts and Titians, to name just a few.

At the time of these infamous shopping sprees it was estimated that 30% of the population were struggling on barely $200 a year, not enough to afford the barest necessities of life, such as food, shelter, clothing and medicine – the very things that Imelda, in her new capacity as Minister for Human Settlements, was expected to provide.

In their 21 years in power, it has now been established, the Marcoses salted away between $18 and $30 billion, most of it intended for aid programmes but much of it from personal “donations” Imelda had successfully extracted from intimidated local businessmen. There is no doubt the Marcoses certainly robbed in style, particularly Imelda.

Many of my wealthier friends were constantly receiving visits from the Manila Metrocom, Imelda’s own private police force, with a personal note saying,

“Congratulations! You will be delighted to hear you have been selected to appear at the Palace with a cheque for $10,000, (or shares in your company or deeds to your properties) to donate to my favourite charity.” and it was signed, Imelda Romualdez Marcos.

It was a novel kind of reverse lottery.If they refused to cooperate they would automatically receive a visit from the Bureau of Internal Revenue. If this tactic still failed to convince them then their businesses were taken over by one of Imelda’s friends or family.

But, with an armed police escort, threats of imprisonment and promises of in-depth investigations into their business affairs by the tax authorities, few dared to refuse such a subtle and seductive invitation. In fact one of my friends said he received so many of these “congratulation notes” that he wallpapered his entire downstairs bathroom with them.

Parrying questions by American journalists about her extravagances, she explained:

“I must confess that once upon a time Marcos’s family and mine were oligarchs. But we are reformed oligarchs. The Romualdez family has been in office for many years and thank God there is a family who is willing to serve our country. Thank God they know how to make money. Otherwise if Marcos did not know how to make money before, what experience would he have to make his country prosper? The United States is ashamed that it is rich. Why should we be ashamed? We have some gifted members in our family. Good. They want to serve our people. Wonderful!”

She left the reporters as perplexed with this explanation as she did a group of scientists from the august National Academy of Sciences whom she invited to Malacanan Palace to discuss energy conservation. When they arrived she said energy conservation bored her and she really wanted to talk to them about love, truth, justice and beauty. She then entertained them with folk songs, beautiful women, local celebrities, a banquet dinner and dancing.

After the sumptuous meal she took them upstairs and spoke to them for three hours. She told them about her project of giving each prisoner a rabbit, a dog or a plant to love. She then drew a circle on a blackboard representing the universe. She made a hole in the circle and drew some lines. She explained that this represented where cosmic forces entered the Philippines:

“And my scientists tell me,” she said, “that these forces are so powerful that we can use them to protect you – our American friends – against Soviet missiles!”

Imelda’s forays onto the world political stage were equally successful in grabbing the

international headlines and she was dubbed, “The Iron Butterfly”. A typical trip abroad might include a visit to Tripoli to dissuade Colonel Gaddafi from financing the Moslem rebellion in the Southern Philippines (for which she later campaigned to receive the Nobel Peace Prize), a short stay in Moscow with the intention of sending shivers down the spines of the domino-theorists in the State Department, an exhaustive tour of Cuba accompanied by Fidel Castro, who fell for her charms. And then, homeward-bound, with a final stopover for an audience with the Pope, to remind him that even an impoverished, developing nation like the Philippines can be the fifth largest contributor to the Vatican coffers.

To prevent boredom at home she pursued her “edifice complex” with a vengeance. Perhaps, like the Pharaohs, she intended to leave the world monuments to remember her by. She built the Cultural Centre in 90 days as a venue for the Miss Universe contest, then came the International Convention Centre to give a forum for overseas investors and businessmen, a Folk Arts Centre, ready in time to accommodate the Ali-Frazier “Thrilla in Manila” world heavyweight fight, a fortress-like Metropolitan Museum to house her personal collection of paintings, a University of Life, a Heart Centre for Asia, a Lung Centre, fourteen luxury hotels and a coconut palace to accommodate her jet-setting guests and to permanently display – although not to the general public – her priceless collection of jewels and Russian icons.

But the building that tops them all is the Parthenon-like structure dominating the center of Manila Bay and housing her Film Centre, built for an international film festival, conceived by her to rival Cannes.

I watched mesmerized as the mammoth building was constructed in 90 days by literally thousands of underpaid workers struggling day and night to make sure it was completed on time.

A week or two before the grand opening a catastrophe happened. A huge section of the native bamboo scaffolding collapsed resulting in hundreds of workers plummeting headlong into the quick-drying cement. And as their fellow workers scrambled desperately to free the victims, the order came from Imelda that there was no time to dig them out, work must continue otherwise the opening deadline would have to be postponed and her foreign guests would be “disappointed”.

Offending legs and arms that were not completely buried by the cement were ordered to be chopped off and destroyed while the widows and families started assembling at the scene for an impromptu candlelight vigil which was to last for several months.

The opening was a surreal event. Cocteau himself could not have dreamt up a more grotesque one. Despite violent police attempts to remove the grieving families, the vigil outside defiantly continued. As hundreds of demonstrators were forcibly removed, hundreds more arrived to take their place – a never-ending stream of wailing mourners.

Meanwhile I watched as minor celebrities from the United States and ex-royalty from Europe began arriving at the Centre in their stretch limos, ignorant of the disaster and unaware of the grim reception committee that awaited them.

Despite last-minute threats and financial inducements by Imelda to the hostile workers to finish the building on time, the roof was incomplete on the opening night. And, despite the fact that the rainy season was long over, that particular night, of course, it chose to rain. Journalists huddled to keep dry outside as guests were ushered inside to their seats. Some seats that were exposed to the open roof were already soaked, but there was nothing Imelda could do. That night there was no let up. It seemed to those of us watching the event that heaven was resolved to mourn its dead that night.

Imelda was, as usual, the last to arrive. On stage a chorus of hastily assembled patients from her Heart Centre began to sing as she entered the hall and swept down the aisle. They sang The Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah, “And he shall reign for ever and ever!” Except they replaced the word “he” with the word “she”.

At the end of their song, to the disbelief of the audience, each one stepped off the stage, bared their chests and walked among the front rows of the stalls displaying vivid purple scars from recent heart operations. Shocked gasps were followed by an embarrassed silence. People didn’t know which way to look. The emcee on stage proudly announced that these people had all received their operations at the new Imelda Romualdez Marcos Heart Centre.

At this point, of course, the audience was expected to burst into rapturous applause. But, by this time, the persistent wailing from the mourners outside echoed eerily through the hall as rumours of the disaster began to spread. The bizarre ceremony on stage made the audience uneasy and most gave hasty excuses and left.

By now Imelda’s regular guests included Cristina Ford, the ex wife of the American auto magnate, Henry Ford II, the actor George Hamilton, the pianist Van Cliburn, the chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer and Jack Valenti, President of the American Motion Picture Board. These people she referred to as “my gang” and, given a moment’s notice, they were ready to fly to her side anywhere in the world.

Imelda’s most notorious junket with her “gang” in tow was her trip to Kathmandu in March 1975 to attend the coronation and wedding of King Birendra. Before her flight to Nepal she was entertaining her “gang” and others, including the heart surgeon, Dr. Christian Barnard and the actress Gina Lollobrigida, at Malacanan Palace. But instead of ending the party when it was time for her to leave for the Himalayan capital, Imelda decided to take the party with her – without a thought for foreign protocol or expense.

She commandeered four Philippine Airlines planes, one for food, just in case the Nepalese food failed to please her friends’ palates, one for her entourage, which included six hairdressers, manicurists and medical personnel and two for herself, her family and friends. The trip was scandalous by any standards. A former classmate of the King recalled the dismay at court when, upon her arrival, Imelda walked straight up to the King, completely ignoring protocol and the waiting reception line, which included the King’s mother. According to the classmate, the Nepalese Royal Family was furious as word of Imelda holding her own court in Katmandhu and issuing her own invitations spread through Himalayan kingdom and abroad. But she was only repeating what she had done a few years previously at the Shah of Iran’s party in Persepolis.

During the next few days of festivities Imelda kept close to Prince Charles, whom she realized

would attract most of the media attention. By placing herself at his side she could guarantee she would end up on every television screen and on the front pages of every magazine and newspaper the world over. The plan worked and, although the Prince of Wales remained impervious to her charms and refused Imelda’s invitation to visit Manila, another member of the British Royal Family would accept later the same year.

Imelda had been hatching plans to play host to a member of the British Royal Family for almost three years. And the fact that she had been refused by both the Queen and Prince Charles did not dull her determination but she also came to realize she would have to settle for something less. Imelda knew Princess Margaret’s weakness for attending extravagant parties and she planned to create the biggest party of all, one that the jet-setting Princess could not possibly refuse. She employed an Italian art dealer, Mario Durso, an acquaintance of the Princess, to convince, coerce or inveigle the Princess to visit Manila.

Finally, towards the end of 1975, her opportunity arose. Princess Margaret was due to fly to Papua New Guinea to represent the Queen at the Independence Day ceremony. The Princess asked Durso to inform Imelda she would be prepared to visit Manila on her return journey. This was the moment the First Lady had been waiting for. This was the time for her to pull out all the stops. She pleaded with Durso to insist that the Princess arrive in Manila on a Sunday so she could command all Manila’s schoolchildren to line the streets from the International Airport to Malacanan Palace waving British flags.

Plans forged ahead at full steam. No expense was to be spared. Imelda’s coterie of blue-frocked girlfriends, known as the “Blue Ladies”, were dragooned into preparing bacchanalian feasts for the Princess, at least one for every night of her visit. A suite of rooms in Malacanan was hastily redecorated to the Princess’s taste and Imelda’s international celebrity friends were invited, all expenses paid, to come to Manila to join in the fun. Manila was festooned with Union Jacks for almost a month. For the first time British television shows outplayed American ones on local television stations. And shops, such as Rustans Department store, owned by Imelda’s best friend Glessie Tantoco, were inundated by British goods, British fashions and British food.

Bulldozers were hastily put to work razing squatters’ huts on the route from the airport to the Palace. However, as had so often happened before, no sooner had the shanty homes been demolished and the squatters driven out, than the cardboard and corrugated tin houses went back up again. This scenario occurred every time Imelda expected a visit from a celebrity, foreign dignitary or overseas businessman. The result was always the same. Imelda would have a high white-washed wall erected around the whole area so that nobody could see in and the squatters couldn’t get out. Inevitably, the hapless residents inside would be forced to hack their way through the wall so it ended up looking like a giant honeycomb.

But, despite all these preparations, all did not go according to plan. The Princess fell sick with flu in New Guinea and informed the British Ambassador, Sir John Addis, that her arrival would be delayed by a few days.

Sir John, who had become a good friend and travelling companion of mine, later told me:

“I dreaded telling Imelda that the Princess would not be arriving on Sunday as planned but, most likely, on the following Tuesday or Wednesday.” I could tell Sir John was relishing this story. “You can imagine Imelda‘s reaction,” he smiled, “She was not amused. All her plans had to be rescheduled.”

I could visualize the scenario. But even Sir John who was a diplomat of the old school, a quiet scholarly man, a world-respected authority on China and Chinese porcelain, became almost apoplectic whenever he discussed Imelda.

“What about the schoolchildren?” I asked.

“Ah, yes, the schoolchildren!” Sir John grinned, “You see I wasn’t able to give Imelda the exact day Her Highness would be arriving in Manila. And well, even

she couldn’t declare a national holiday for a whole week, could she?”

“So who waved all those thousands of imported British flags?” I asked.

I had heard rumours about this incident but I was eager to know from Sir John what really happened the day the Princess arrived. Sir John laughed. Despite a distinguished career in the Foreign Service and, as such, trained to be tactful at all times, he could never resist gossiping with me about Imelda. We were sitting beside the lake at his magnificent garden in Kent and, as he had many times during our long friendship, Sir John was prepared to let his guard down.

“Well, there was an argument as to whose car the Princess would travel in. Imelda obviously wanted to meet her at the airport and take her in her own car back to the Palace. However, I had to explain to her that technically the Princess was a guest of the Embassy and, as the Queen’s representative in the Philippines, I would be expected to meet her at the airport.”

I giggled. I could imagine the scene.

“Imelda must have exploded!” I said, “She’d been planning this for years!”

“She was definitely not happy.” Sir John chuckled. “I tried to cater to her vanity by saying that, as First Lady, protocol dictated that she and the President should wait and greet the Princess at the Palace. Eventually, she relented but not without a struggle. So off I went to the airport followed by a phalanx of limousines. I noticed that Imelda had been hard at work because the route was lined with thousands of men in grey overalls holding the British flag.”

Intrigued I asked, “Who were they?”

“Well, deprived of the schoolchildren, Imelda had replaced them with inmates from all the prisons around Luzon! Sir John giggled. “And, wait for this, Caroline, just in case the prisoners decided to make a communal bid for freedom she had sharpshooters from the Army and the Manila Metrocom hanging out of windows and suspended in the branches of trees above with rifles aimed at the them.”

“What was the Princess’s reaction to all these men in identical outfits?” I asked, “Did she realise who they were?”

Again Sir John laughed. “She looked amazed and then turned to me and in her very upper crust voice, asked, “Tell me, Sir John, are they all civil servants?””

“And what was your answer?”

Still chuckling from the memory, Sir John replied, “Well I said,“In a manner of speaking, Ma’am, yes they are!”

In 1986, during the “Peoples’ Revolution”, as it came to be called, newsreels and photographs

emerged from Manila’s presidential palace, Malacanan, that filled viewers with a mixture of fascination and horror. There were the rows upon rows of discarded shoes, the obscene mountains of unused cosmetics, the 3000 bras and panties, leading most observers to ask themselves, who was this woman who called herself the “Goddess of all the Arts” and the “Star and Saviour” of the 54 million Filipino people?

Imelda never expected to be forced into exile. She had lived with delusions of her own infallibility for twenty-one years – and the US government was, in most part, to blame. While Imelda “shopped till she dropped” and her husband imprisoned, tortured or killed any dissenter, agitator or critic, successive US Presidents went out of their way to praise and support them both.

In 1980 former President Nixon called Imelda “our Angel of Asia.” In 1981, after a blatantly corrupt election, Vice President George Bush Sr told the couple:

“We just love your adherence to democratic principles and the democratic process!”

And, during the Marcoses state visit to Washington a year later, President Reagan heralded their dedication to “improving the living standards for all their countrymen” and called them, “Nancy’s and my greatest friends and America’s greatest allies in Asia.”

It seemed then the couple could do no wrong in the eyes of each United States government, convulsed as it was in the aftermath of Vietnam and ever fearful of Henry Kissinger’s “domino theory”, a theory that never stood up to serious scrutiny even then.

In fact Marcos and Imelda never even considered themselves mortal. In one issue of Playboy magazine, recorded during the Marcoses exile in Hawaii, they were asked the question:

“Do you think of yourselves as Gods?”

To which Imelda’s immediate reply was:

“Yes, because we are on a divine mission to return to the Philippines and reclaim our destiny.”

The ex President then chipped in:

“We are part of the achievement of being a God. That is what we are about now. An ordinary mortal would not be able to stand it. All of our statements now have to prove that we have not gone back to being ordinary mortals.”

But robbed of her personal fiefdom and her bottomless Treasury, with her own Swiss bank accounts frozen and nowhere to display her priceless jewels, Imelda Marcos presented a pathetic figure, hardly that of a deity. The Iron Butterfly’s wings had been severely clipped and, with it, her freedom to jet around the world at will. Her hard-earned memberships to the exclusive playgrounds of the privileged few had been withdrawn. Doors, once open by the rich, titled and powerful had been firmly slammed in her face. She complained that in Hawaii her telephone never rang and friends were always out when she called. The “enchanted fairytale” as Imelda once described her life, was over but, according to the Playboy interview, she saw it only as a “temporary intermission.”

When her husband died in exile, Imelda’s only dream for herself was a triumphant return to Manila. Forty years ago she had arrived in Manila with a beautiful young face, a dream in her head and five pesos in her pocket. Again she would arrive in Manila, this time broken but unbowed. She vowed she would seek the Presidency “for all those supporters who have anxiously awaited for my return.”

From her exile in Hawaii she made this promise to them. “I’ll go back with only five pesos and I’ll make billions and billions of dollars, because what I do comes from the heart and the brain – and I’ve got both!”

But the support she expected had evaporated in her absence. The Philippines had moved on. Ferdinand’s corpse, she was told, would not be welcome, his body would have to remain in Hawaii. The housewife, Cory Aquino, who had become President by default negotiated Imelda’s return in exchange for access to some of the stolen money.

So Imelda bided her time, staging her political comeback to coincide with the inauguration of her former friend, the actor-turned politician, Joseph Estrada, an alcoholic womaniser who abused his position to such an extent that he, too, was toppled within his second year. And, despite, crawling down the aisle of Manila’s Cathedral on her knees to beg God’s assistance in returning her to power, Imelda has reluctantly had to give up all ideas of obtaining the Presidency and setting in motion the family dynasty that was her husband’s dying wish.

Later, when asked about this, and other similar, tactics by Fortune magazine, Imelda simply shrugged:

“I’m like Robin Hood. I rob the rich to make my projects come alive. It’s not really robbing. I do it with a smile !”

Her projects included literally hundreds of buildings. Palatial homes all over the world for her and her family, luxury condiminiums and office blocks, larger-than-life monuments of herself and her husband, numerous “love bridges”, health centres and art centres and a string of shopping malls and five-star hotels.

Imelda’s response to accusations of extravagance was simple:

“In the material world,” she explained coyly, “where everything is valued, when you commit yourself to God, beauty and love, itcan be mistaken for extravagance ! But I have never been a material girl. My father always told me never to love anything that cannot love you back!”

And these words from a simple girl who went out of her way to obtain the world’s largest uncut diamond from Harry Winston, obviously so it could love her back, and not so she could outshine Elizabeth Taylor !

Imelda’s extravagance knew no bounds. She grabbed everything, bought everything, hoarded everything. Her excuse was that she was doing it for her “little people”. Like the “meek” in the Bible, she assured us, they would inherit it all.

“Everything I have is theirs,” she informed us journalists one day:

“I am their star and their slave. No matter how poor they are, whenever they see me they smile and they are happy!”

POSTSCRIPT: Just thought I would add this as it strikes me as funny – and, typically, Imelda.

Another postscript by Rappler. Following the outrage by ex-alumni of Ateneo inviting Imelda to the Universitiy recently. The photograph of her with the alumni went viral and many wrote in to protest. “Did the alumni remember those students who died during the Marcos regime?” I understood their anger. I knew Eman Lacaba, the young poet, very well. He even wrote a poem dedicated to me. He was hauled away to Camp Crame one day never to be seen again. Shame on Ateneo. The alumni has since issued a statement. You can read the full story here:

Yet another postscript: An off-Broadway musical, “Here Lies Love” about the love affair and conjugal Presidency of the Marcoses is getting a rerun at The Public Theater in New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment